Artist portrait by Mark Daybell

Artist portrait by Mark Daybell

Jody Zellen

Los Angeles based artist

Interview by Mark Daybell

MARK DAYBELL: It is July 16, 2019. We’re here with Jody Zellen at her Santa Monica studio. Jody, in terms of medium, your work is very diverse from traditional forms such as drawing and painting to very 21st century forms like mobile apps. In your mind what connects the work?

JODY ZELLEN: It’s all connected conceptually even if some of it is by hand and some of it is digital. I might sit here and doodle away and make a drawing. But then I might scan that drawing and duplicate it and collage it, and it becomes a digital photograph. And then I might pull it out of that and drop it into an animation program. And then it becomes an animation and then maybe a series of animations gets strung together to be in a video projection. And then it’s like, “Oh well that’s big, and that’s on a wall. And I want it small and intimate so maybe I can make it into an app.” It’s an unconscious chain of events that one thing leads to another that leads to another.

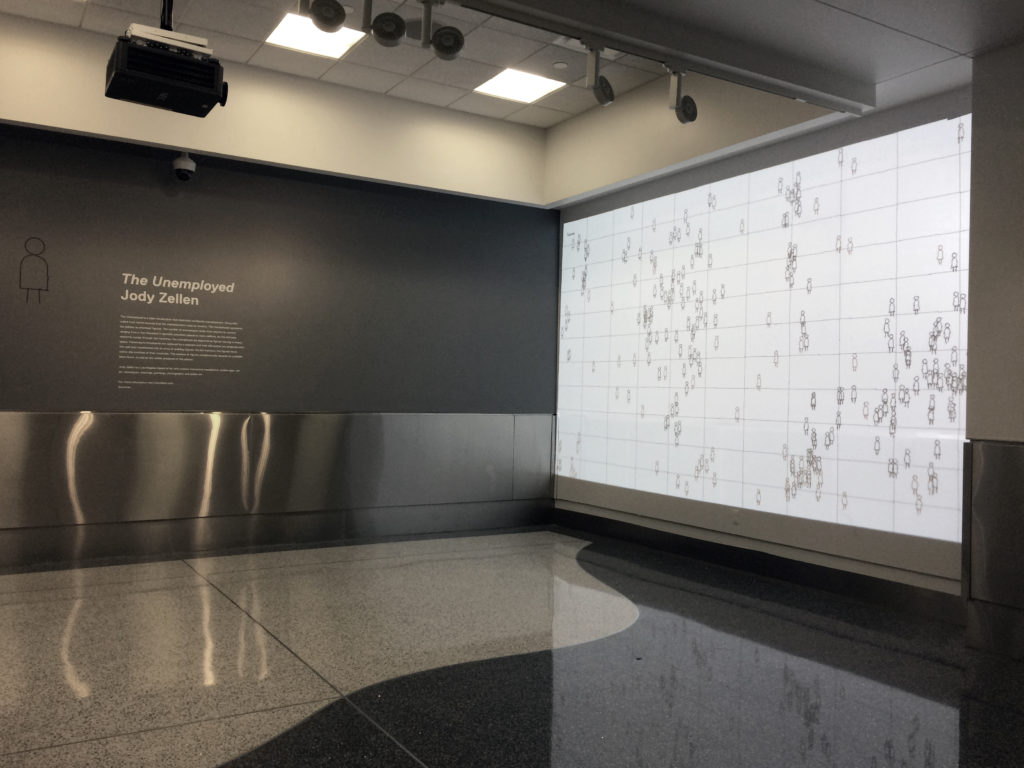

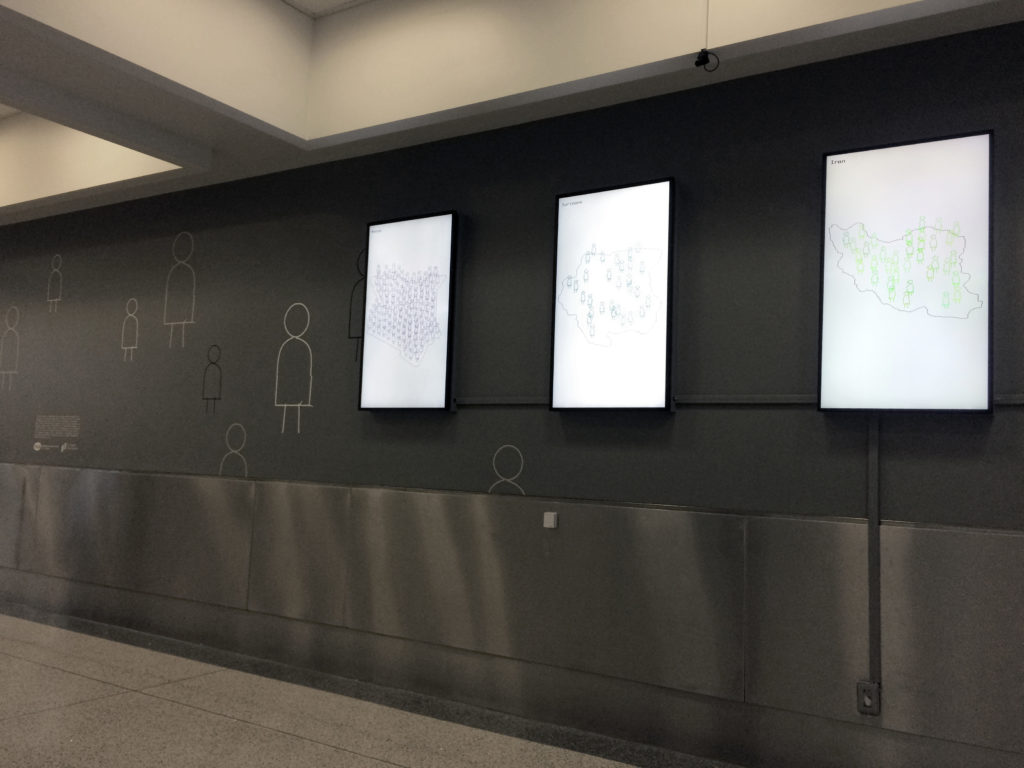

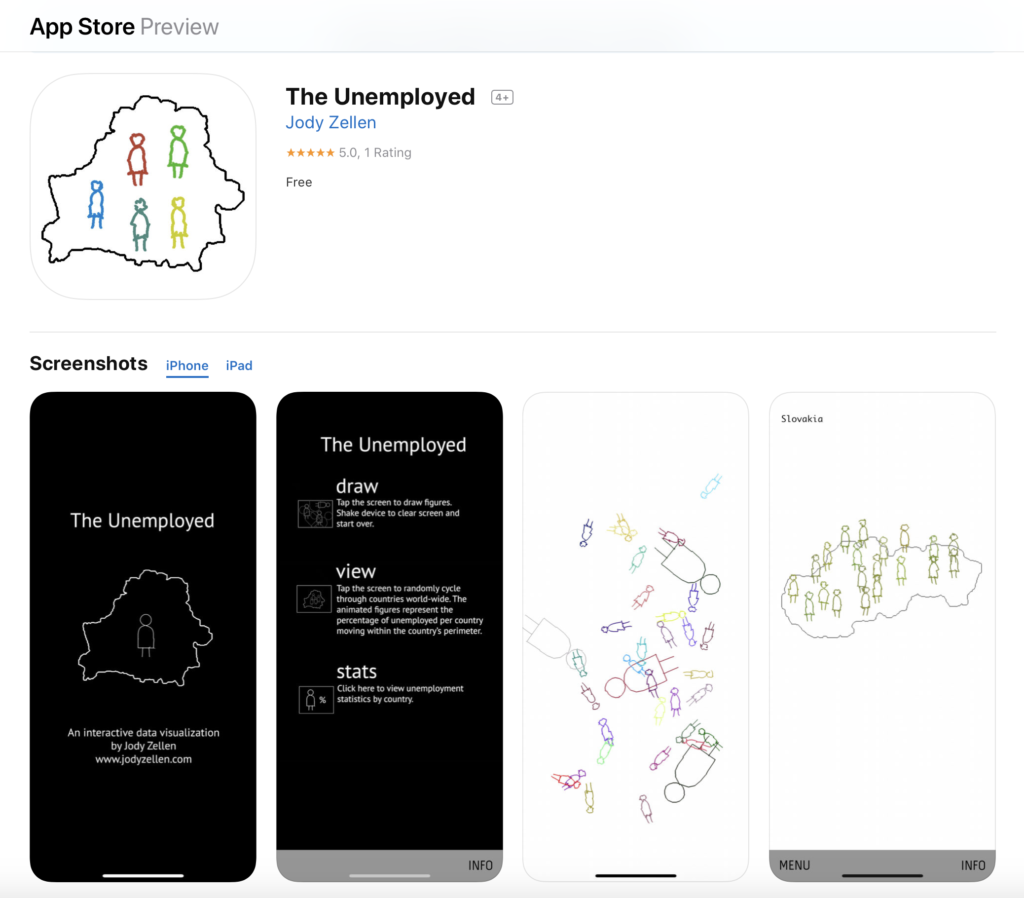

The Unemployment (installation view detail) 2019

The Unemployment (installation view detail) 2019

The Unemployment (installation view detail) 2019

The Unemployment (installation view detail) 2019

DAYBELL: What initially attracted you to art and art making?

ZELLEN: As a kid I was taken to the museum school and given art lessons and did drawing and painting. I think I started doing photography when I was in high school. I continued with photography as well as drawing and painting. I also began studying art history.

DAYBELL: Just a little follow up. You said you were “taken to art school.” Was it your parent’s initiative or did you ask them to take you?

ZELLEN: I think it was probably their initiative. Growing up my mother used to go to painting class and weaving class. She’d do different kinds of crafts. I have no recollection if I said, “Can I go to art classes on Saturday morning?” Or my parents said, “We’d like you to go to art classes on Saturday morning,” or even if it was Saturday. But I definitely was involved in making things from early on.

DAYBELL: Did you receive a formal visual arts education?

ZELLEN: I took art classes through high school and into college, that included basic drawing, painting and photography. I would say, yes, that was formal, plus going to museums, galleries, and studying art history.

“I think I’m one of those people who works much more spontaneously and intuitively and doesn’t think so much about what my process is or what the research is going to be and what the outcome is going to be. It’s much more organic.”

DAYBELL: You also have a degree in computer science?

ZELLEN: I got an MFA in ’89 from CalArts. My concentration was photography, but I don’t think that meant anything. It just meant what school you were in.

Later, I wanted to do interactive installations and I felt in order to be able to do what I wanted to do, I should be able to do my own programing. So, I investigated ways of doing that. NYU has a program called the Interactive Telecommunications Program, ITP, that when it started I think was really successful in teaching visual artists how to do computation and how to program. I think now the school has flip-flopped and the people who go to it come out of computer science and engineering. They want to be able to take those programing skills they already have and begin to use them in a more creative way. The program teaches them how to think visually, on a very base level. I felt like I fell through the cracks because I really wanted the programming.

DAYBELL: What does your practice of creativity involve? Can you talk about some specifics?

ZELLEN: I think I’m one of those people who works much more spontaneously and intuitively and doesn’t think so much about what my process is or what the research is going to be and what the outcome is going to be. It’s much more organic. But I also collect things and a lot of the work has stemmed from collecting pictures, or collecting pictures from the newspaper, or collecting headlines from the newspaper, and sitting on these different kinds of archives, and then eventually figuring out ways to make something from them.

As I mentioned, one thing could lead to another to another to another. But, for the most part, I think my work is somewhat spontaneous. If I’m making something digital or making an animation, it takes time. Otherwise, the work is quick. I don’t over analyze things. I don’t think, “Well, could I do it this way? Could I do it that way? What might be better?” I don’t have that kind of dialogue with myself. I just make it. And if it’s a bad one then I throw it away. I don’t show it to anyone. If it’s a more successful one, it’s like, “Oh that looks good. Maybe I could try this or try that.”

DAYBELL: You mentioned you keep an archive; can you tell me a little bit about that part of your process?

ZELLEN: Before everybody had a phone and a computer, I used to save images almost daily from the newspaper or from magazines. I would rip them out and throw them in a cabinet to store as raw material. If I was reading something, I would write down phrases or words or captions that I thought were interesting that eventually I might use for something else. I think that’s been the basis for a good part of the practice. For a long time I stayed away from using images I found online but eventually I shifted and began to save picture from digital sources as well.

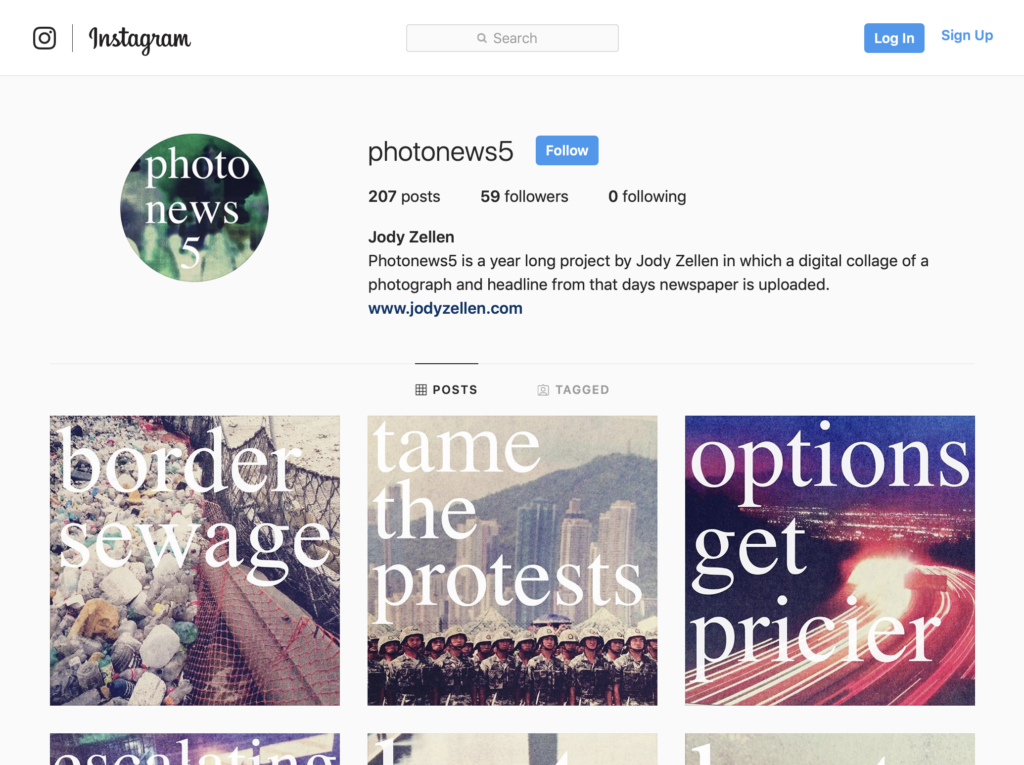

Currently I’m working on a project where I’m making a photo collage everyday by using my cellphone to take a picture of the printed version of the newspaper and then typing on top of that image a fragment of its headline and then posting it to Instagram. I started that in January. It’s going to be a yearlong project.

DAYBELL: What’s the @ for that project?

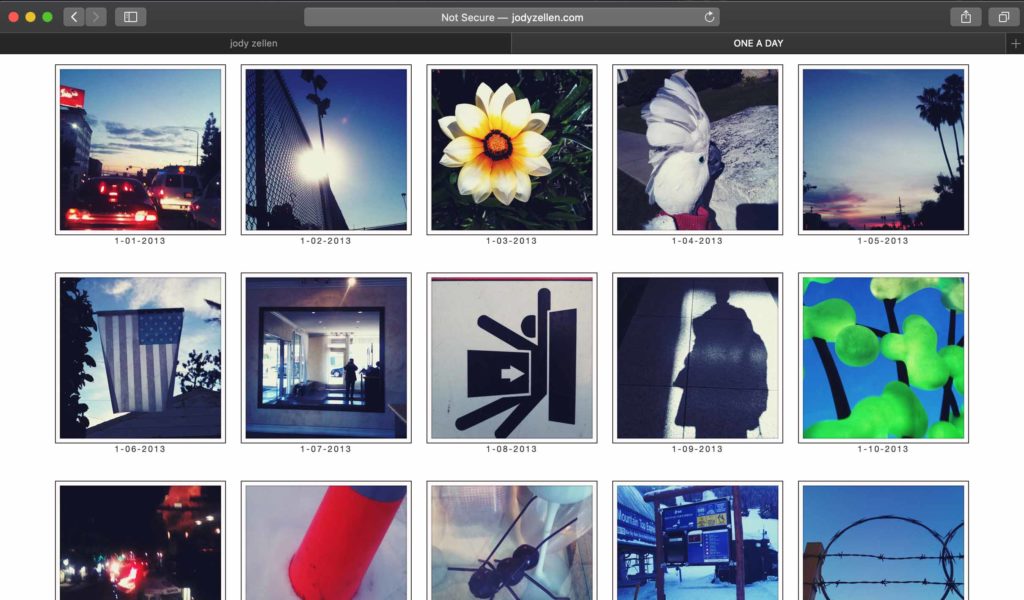

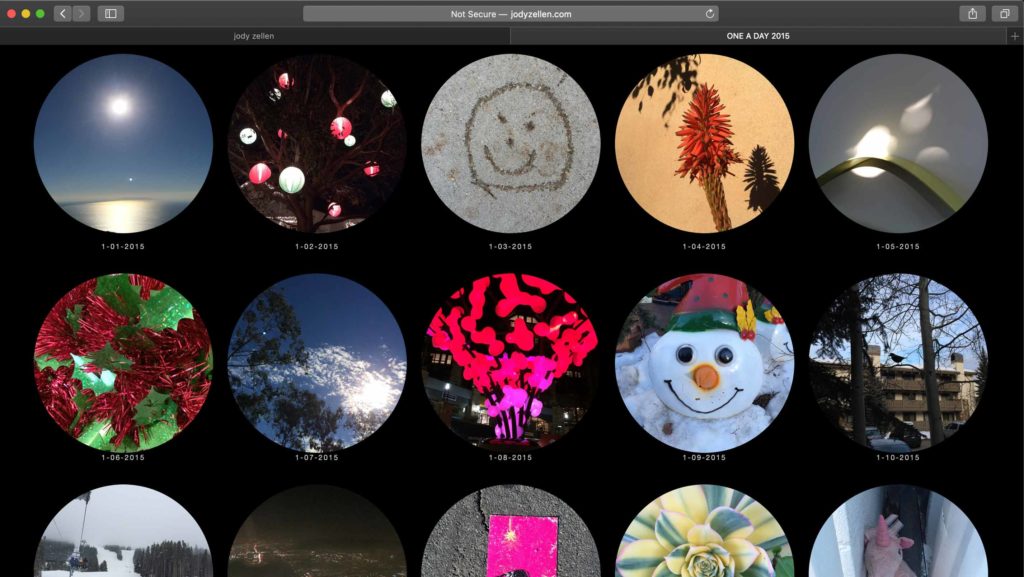

ZELLEN: @Photonews5. In terms of process, making things from newspaper images and newspaper headlines has followed me for many, many projects. I also have done a lot of projects that are daily. I do a daily drawing. I’ve been doing that since 2004. For many years, I would take a picture every day and at the end of the year I will make a website that had one picture that represented each day.

photonews5 2019

One a Day 2013

One a Day 2015

DAYBELL: Much of your work is commissioned, can you talk a little bit about that process and how your creative practice might differ from your non-commissioned work?

ZELLEN: Public art commissions are typically a collaborative process with the agency that commissions them. I did a project for a police station and I thought to myself, “Oh great. I can do a piece about the history of violence in Los Angeles.” But then I realized that may not really go over that well, I’ll need to tone it back. So, I thought, “I want them to accept the idea so maybe it will be about the architecture of the area.” With the West Valley Police Station project, I met people who had access to an archive of police photos from the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s. So, I was able to include something that was a little bit more inline with my non-commissioned work. Those kinds of projects are often compromises because you don’t always get to do what you think you want to do. It’s a lot of back and forth.

West Valley Police Station (detail) 2005

West Valley Police Station (detail) 2005

West Valley Police Station (detail) 2005

West Valley Police Station (detail) 2005

DAYBELL: Can you talk about how you begin a project?

ZELLEN: So much of what I do is sitting still at the computer. I might begin a painting project because I didn’t want to be at the computer anymore. I might ask, “What can I do with these images that I’m making in the computer to get them out of the computer and be more active.” So, I started to project the image and to paint it. And then it turns into a whole series of paintings.

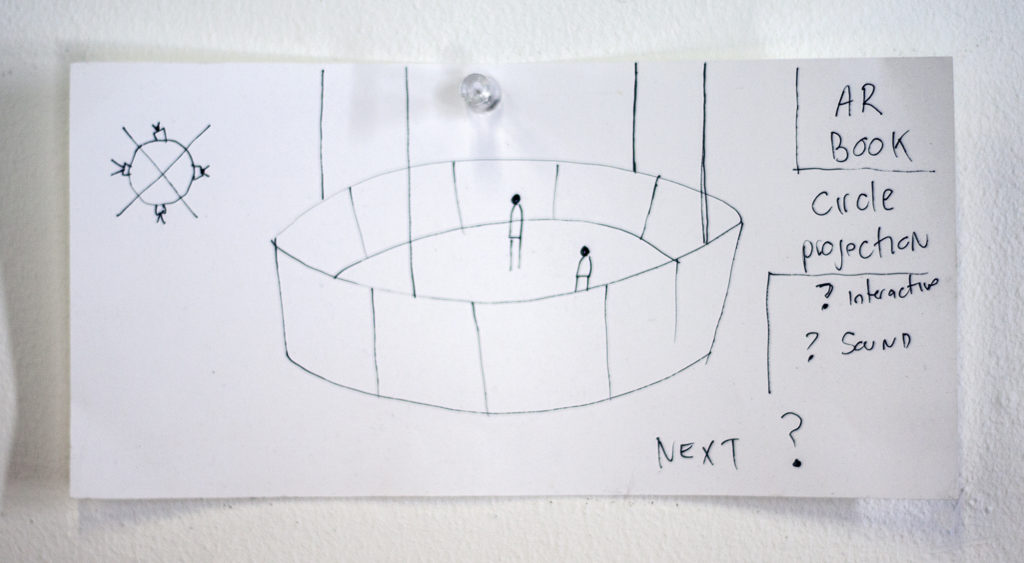

DAYBELL: How do you record your ideas for projects?

ZELLEN: I don’t really. I keep an active notebook with doodles and lists of things I need to get. But I actually don’t plan things out in a notebook. I mean sometimes I do— like on the wall here—is an idea for an installation. And there’s a word that says, “Next.” So that’s how I have planned it out. That’s a concept drawing for the installation that I want to do next, diagramed on a scrap of paper. Will I ever be able to realize it? I don’t know.

Installation Sketch

DAYBELL: It sounds like your practice of recording the ideas is the work?

ZELLEN: Yeah, strangely. Some of these pieces, they’re just photographs of graffiti that I’ve taken walking around in different places. I photograph things that catch my eye. But then I thought, “Okay, I could combine those with some drawings.” But I really wanted them to become much more active. So, that whole project was a catalyst for augmented reality where if you look at the pieces through an app on the phone, they become animations. Like this one, it’s the combination of found graffiti and then my drawing on top of it.

“My process is very obtuse and not super self-critical. I just let things happen. I will almost never say, ‘Oh, I shouldn’t do that because it’s a bad idea.’ or, ‘I shouldn’t do that because someone else already did it.’ I just try it. And if it works, it works. If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work.”

ZELLEN: At the moment, I have started to explore a new idea by just playing around. I didn’t write down the idea, it’s much more intuitive…I was looking at some iPhone photos of graffiti from a recent trip, thinking about how I could combine them in a drawing and then use that drawing as a point of departure for an animation that would be activated via AR. My process is very obtuse and not super self-critical. I just let things happen. I will almost never say, “Oh, I shouldn’t do that because it’s a bad idea. Or I shouldn’t do that because someone else already did it.” I just try it. And if it works, it works. If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work.

The Human Touch (installation) 2018

DAYBELL: What is the role of chance in your creative process?

ZELLEN: A lot of projects are about chance. When I am collaging photographs with my own line drawings, I will try a lot of different combinations. First this one, then that one. I might actually go through a file of 100 images and suddenly it gels— it’s, “Oh this one works, great.” It’s not thought out, like, “Well I want to connect this line to this line.” It’s just, “There it is.” And it works.

I have also created numerous projects that are about random juxtaposition. A few of my iOS apps allow you to click on different images or texts until you get a combination that might coalesces and resonates for you. My approach was, “Let’s bring these four completely unrelated things together and see if you could make them resonate.”

I have another app called News Wheel that changes in real time on a daily basis. First it brings in sections from nine printed front pages. These fragments are composited together in a pie shape with nine slices. When you tap the screen, it spins. When you tap the screen again, it stops. Each time the wheel stops a current headline drawn from a RSS feed from one of the nine news source appears on the screen. I am interested in how the individual headlines resonate. I often think: “that’s an amazing headline. And look at how it works with that particular image.” For years I saved screenshots of these combinations. Eventually, I had so many interesting screenshots, I decided to create a book. I also produced a series of lenticular prints from this imagery. I want to bring back some kind of dynamic and animated quality to the project in still form and happened upon the idea of making lenticular images.

News Wheel (in collaboration with Daniel Rothman) 2016

DAYBELL: How do you recognize a good idea?

ZELLEN: I don’t know. I don’t think about it. I don’t ponder the question, “Is this a good idea or is this not a good idea?” But rather, I ask if this is an idea I want to follow through with. Let me see where it leads me and then maybe rely on other people to say, “Oh wow. That was a good idea. I like that.”

DAYBELL: Interesting, sounds like you don’t really edit your ideas because you’re not trying to be critical, you’re just trying to follow through, which might lead to 10 other things, it might not. You’re going to trust your instinct, your intuition, your practice.

ZELLEN: Right. So if I sat here and said, “Drawing other people’s graffiti, wow, that’s a really stupid idea. And why would you want to do that? And no one’s going to care.” I mean…then I wouldn’t do it. I feel like rather than being self-critical, I think just explore it, have fun with it. Don’t badger the idea. Don’t pick away at it. It’s not necessary. I don’t feel I’m all that theoretical in my thinking about the work. Someone else can come and talk about that. I’m not suggesting the work doesn’t have any content or any depth, but I don’t explore all the parameters of an idea and have all that figured out in order to make something. I just don’t want to go there.

“I feel like rather than being self-critical, I think just explore it, have fun with it. Don’t badger the idea. Don’t pick away at it. It’s not necessary.”

DAYBELL: How do you know when a project is finished?

ZELLEN: Maybe when I feel I’ve exhausted all possible permutations. Or, if there is a fixed structure then it is easy. I have made a number of artist’s books that are 40 pages so when I’ve created 40 images that work together, the project is finished. I guess then there’s some kind of closure. I don’t need to necessarily go back and revisit it.

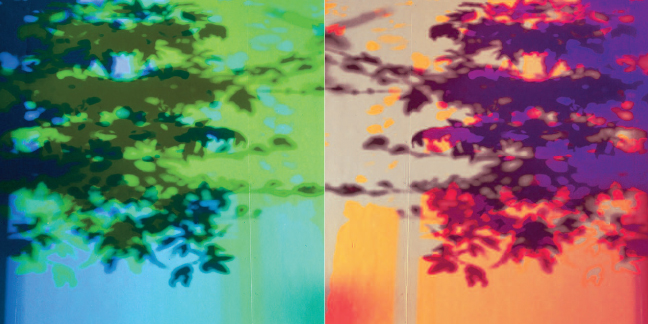

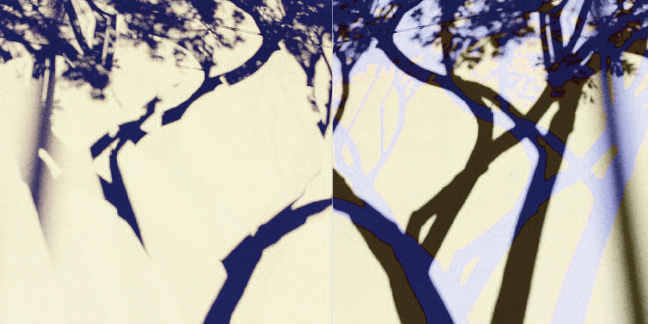

Shadow Trees, 2019

Shadow Trees, 2019

Shadow Trees, 2019

Shadow Trees, 2019

Shadow Trees, 2019

ZELLEN: But some projects are never finished. They just go on and on. Or they have specific time frames like a year.

DAYBELL: What inspires and informs your creativity?

ZELLEN: I read a lot. I see a lot of shows. I walk a lot and I look at things. And I run. Those activities sometimes help to generate ideas. Also, watching the sunrise or watching the sunset, or seeing the pink sky can help generate ideas. Even though my work has almost nothing to do with nature, nature plays a big role in forming how I think about things.

DAYBELL: What advice would you give emerging artists?

ZELLEN: It’s an incredibly difficult profession, so much of it is based on luck. I think it’s important to figure out some kind of fallback because very few people make a living from their practice as a fine artist.

More of Jody Zellen’s work can be viewed at: jodyzellen.com

Article edit by Mark Daybell

THE PRACTICE OF CREATIVITY

©2015-2020 All rights reserved