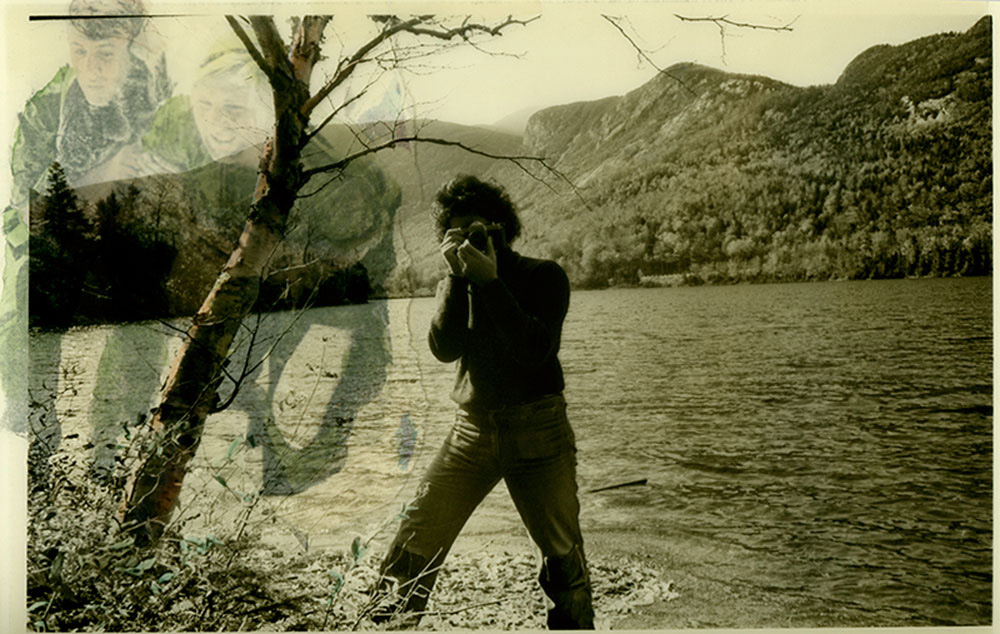

Artist portrait by James Jenkins

Artist portrait by James Jenkins

Eileen Cowin

Los Angeles based artist

Interview by James Jenkins

JAMES JENKINS: It is May 26, 2016 and I am interviewing Eileen Cowin in her studio in Los Angeles,California. Can you tell me a little bit about your artwork?

EILEEN COWIN: I’ve always been interested in storytelling and narrative. I would say that I wish in my next life I’d love to be a writer. I love reading, I love novels, I love people who can tell a story and do something with language that’s really transformative. Something that transports you to a place, a feeling, an emotion, but I can’t do that. I’m not good at that but I keep trying. In my work I create narratives, and I’ve been working that way for years. Even going back and looking at work from college, the way I would combine things, like turpentine transfers with the photographs I made. That’s what I’m doing, I’m creating little stories, little narratives. I’ve been doing it for over 40 years now.

JENKINS: Can you talk about some of the recurring themes in your work?

COWIN: I’m sometimes interested in how you take the ordinary things that we think about, and fuse them with the sense of anxiety that we all feel. I used to say I don’t do in your face work, I do under your skin work. Especially now in today’s culture, we all have a lot of anxiety. I certainly do with the election and all that. Just things like that. I try to explore that.

“I used to say I don’t do in your face work, I do under your skin work.”

I know desire when I see it ©2016

COWIN: Going back to the work that I did even in graduate school, it was during the Viet Nam War and I remember, I had been photographing the interior of people’s houses and the turpentine transfers I put behind it were all from magazines, some of it war related, some of it not, some of it related to women’s movement, just a lot of things that were happening at the time. You see these images that look like they’re coming through the walls of people’s houses. My work isn’t like that now, because I’m not doing that kind of transparency related process, but I do feel that I’m interested in that kind of ordinariness and the kind of rubbing up against cultural anxiety.

New Hampshire, 7 x 10 in. ©1971

JENKINS: Do you make art every day?

COWIN: I can’t say I make art every day. Do I think about it every day? Yes, I do. I think about it every day. I come to my studio pretty much the majority of my time except on the weekends. I try to have family time.

JENKINS: What does your practice of creativity involve? Can you talk about some specifics?

COWIN: You mean how I get started thinking about a project?

JENKINS: Yeah, or maybe how you approach a project, or how a project unfolds.

COWIN: Sometimes to avoid really getting started I have what I call my research period. I will look at books. Two weeks ago, I decided I needed to look at works by Durer, so I went to the library, I got a book. I don’t know what made me think of it but I had seen some pictures of his. One’s called the Great Turf, one’s called the Small Turf. Then I went and I started to look at portraits of his and so I have this process, that’s how I usually start off. Even for this big public art project that I’m working on now, I bought two graphic novels, just to look at the way they frame to see if I can get any ideas about that dynamic framing. I’m doing these narrative strips and how things move from one to another. When I start what I call my research, I’m looking at painting, I’m looking at books on films, I’m looking at stills from film, I’m looking at drawings, I’m looking at a lot of different things like that.

JENKINS: How do you record your ideas for projects?

COWIN: It’s a little haphazard, I wish I was a little more organized. I have these little notebooks. I love notebooks, I buy tons of notebooks, I just bought 3 more little notebooks. I have little ones I carry with me and then I have what I call a project notebook. For each project I have a notebook and I will write notes, quotes from articles and maybe add drawings -whatever I think would relate to the project. Of course, I have my phone and so then I have notes in my phone. I also like little index cards. So, I have index cards everywhere. I have the notebook, the notes on my phone and the index cards. That’s what I mean, it’s a little haphazard. Then I’ll think: I know I wrote that down but where is it, is it in the notebook, is it in the phone, is it on some card?

JENKINS: Over the course of a photograph, is there a structure of your creative process?

COWIN: When I was working on that early family series in the early ’80s I would start that process of looking at books, books on theater, film, other people’s drawing, paintings and then I would do drawings. I had those on notecards, that’s what I used mostly, the notecards. Each image had a drawing on a notecard and then I would write what I needed for props or needed for clothing. I remember a friend said to me, “You know, you could veer from this. You could say, okay, this is what your drawing looks like but you could also change it a little bit.” I thought, oh yeah, I can do that. I think because I was using a 4 by 5 camera it wasn’t the same as using a digital camera where you could take 42 pictures. With the 4 by 5 you had to be a little more economical about it. I don’t mean financially economical, but you just weren’t sitting there with 30 film holders or you were going to do 20 variations on a scene. I would probably do 1 or 2 variations on a scene then.

From the series Family Docudrama 20 x 24 in. ©1980-83

COWIN: That was then. Now, when I’m working on the Metro public art project I’m using a digital camera and I have to say that’s really helped me a lot. It’s freed me up a bit. I had been using it before but now this is really helpful. I will do drawings and I have them on a sheet of paper, almost like a shot list for a film. I have the paper and I have the shots and then I have the notes next to the shots, which will remind me, don’t forget to do this. I will do a number of variations on a shot, either the position of the camera or their gesture or expression, so I will do a lot.

“I remember Aaron Skiskin, my teacher in graduate school, he would kind of feel you shouldn’t look at other people’s process and think that was what you should be doing.”

JENKINS: How do you begin to nurture that creativity when you run into a road block?

COWIN: That’s when I go into, what I call, research mode. Where I start with, okay, pull out the books, think about artists you want to start looking at. Also, when I go to New York, the Met is my museum of choice. I take pictures with my phone of sculptures and paintings and then I go back and study those. Then I think, okay, all right, I’m moving on here with something, I can try to fool around with these things. Also, I try to talk myself out of doing something that’s so enormous. I’ve been doing these things that are 10 feet long, and these big video projections and I push myself to make something smaller – at least try it and see what happens. Sometimes I’ll start small and before I know it, it’s bigger than a bread box. It’s enormous and then I’m like, oh no. Just give yourself permission to say, “let’s just try it here. Let’s just play around a little bit here,” and that’s what I do.

Something Out of the Ordinary (installation view) ©2006 Photo: William Short

JENKINS: Do you feel that you need to be in your studio to access your ideas or where does that happen? Does that happen all day or is it something that you just sort of have as a sacred space where you come in and you work?

COWIN: I remember Aaron Siskind, my teacher in graduate school, he would kind of feel you shouldn’t look at other people’s process and think that was what you should be doing. If you were working in the dark room and you were a big mess, which I was, I was all over the place, well, that’s how I needed to be. When I looked over at someone else who was neat and everything was so perfect, I shouldn’t be looking at that thinking, “oh I should be like that.” The same thing, I come into the studio, I think, “this is what I need to do,” “I need to wander around,” “I need to look at my email,” even though I just looked at it, I need to do all of that. Also, I get good ideas in the car, which is a little hard, because I’m not writing them down but I try to remember them. We’re in the car a lot here in LA so I do get ideas in the car. I could be listening to the radio and hear a story and I’ll think, “oh wow, that sounds pretty interesting, maybe I can do something with that.”

JENKINS: I think you’ve been very successful as an artist and you’ve certainly produced a lot of work. Throughout that process, how do you recognize a good idea?

COWIN: You know what, I don’t always. My husband, when asked, “would you know a good business idea” and I think he said, “If I knew a good business idea, I’d be doing it myself.” I don’t know if I recognize what’s a good idea, because I had been a teacher for so long and I tried to push my students to think things through and not let things go right away. Not just say, okay I did this one thing and now I’m moving on. That’s what I try to do myself. I think, okay, I remember when I did the family work. I don’t know if I said, “Oh my God, this is like the big breakthrough for me,” but then other people said that to me. They encouraged me to keep doing that work and I said, “Okay.” It wasn’t like I hadn’t been working for 10 years before that and gotten into shows and everything, but it was nothing like what happened with that family work. Every once in a while, this is rare, I’ve made an image and I think, this is going to sound so immodest or something, but I’ll say, “I love this image. I just love this image. I don’t know if I’ll ever make another image as good as this image.” I have said that of maybe 1 or 2 images, and then it’s paralyzing, really, when you do that. You kind of go, “Okay, that’s it, I’m done.” Then you have to say, no- just keep on it. I get kind of low when I’m not working. If I’m not making something, I start to feel a little bit low. I don’t always recognize it, I’ll think, “Why am I feeling a little cranky?” “Why am I feeling so low?” Then I know, well, I’m not really making something.

JENKINS: Are you satisfied creatively?

COWIN: Probably not. Probably if I was satisfied, it wouldn’t drive me to keep on it. I think you keep saying, “Okay, I know I can do more with this, I know I can be better, I just keep on it.” I don’t know. If you’re just too satisfied it takes away that edge or something. It’s like when I give a lecture and I’m always nervous and people say to me, “Why are you nervous, you’ve been giving lectures for 40 years, you’ve taught for 40 years?” I don’t know, I always get stage freight, then I think if I didn’t maybe it wouldn’t be as interesting or something.

JENKINS: Have you ever hit a creative wall and how did you break through it?

COWIN: Of course, I have had that. I know I have, I’m not going to say I think I have, of course I have. When you sit there and think you’ve finished a project and it feels so finished that you just feel, well, now what can you do, you’re just so finished. Then there have been other times when people in my family had been ill and then I feel like I can’t even begin to think about making anything. When someone in my family was ill I literally thought, I’m not even going to go to the studio, I can’t even walk in there. I can’t think of anything else but this. Then, things got better and I was able to move on. Even when I finish a project and I think, okay, if you don’t get past this you’re not going to be happy.

You just have to go back to your process. That process of going to films or watching films. Some people will say, “Oh I can watch a movie at the studio or I can just sit here and watch a movie and call it research and I’ll feel like I’m working and that is so cool.” I will do that. I’m a big fan of the Hunger Games and when I watched the first Hunger Games there was a scene with Katniss, the character in the film, she was just terrified and I felt her fear. I literally felt her fear. I was so in awe of her acting in this, which didn’t seem like acting. Then I did a project of 23 actors portraying fear in a video, this 23-channel video piece titled Fear Itself. I just go back to what I know to do, watching films, going back to notes that I’ve taken from books, and looking at paintings.

Fear Itself (excerpt) ©2014

JENKINS: It sounds like you just return to the process?

COWIN: I do.

JENKINS: What advice would you give to young artist?

COWIN: That is a very loaded question because the way, and I use this term that I hate more than anything on the planet, the way the art market is today, it encourages young artists to think in a much different way. To think in terms of product. To think in terms of getting their work out to sell or to be famous or to hit the jackpot in a particular way.

I guess I would encourage artists to try to just do it because they really want to do it. To not be discouraged if they don’t hit that jackpot. That’s the thing. You see these artists, they’re 23 and they’re having a show at the Whitney and so other young artists might think: “Oh my God, I’m 23, I have to try to have a show at the Whitney,” and maybe they won’t. That doesn’t mean they can’t be a productive artist, that they can’t think about other ways to develop their work and get people to see it. If you look over people’s careers, you have to look at them like a graph. Do they have a big spike and then that’s it, or is it a steady thing that goes up and down? You have to think: what is it you want. Some people want the spike, some people want the steady up and down.

“I guess I would encourage artists to try to just do it because they really want to do it. To not be discouraged if they don’t hit the jackpot. That’s the thing.”

JENKINS: Is there anything you’d like to add?

COWIN: It’s like a job. You go to work. My husband used to be an accountant, he’d say, the IRS thinks of artists like sock manufacturers. In a way that’s sort of an interesting way to think about it because you don’t sit there and the light bulb suddenly goes on and you get the lightning strike of inspiration. You say: I’m going to work today. I’m going to go to my studio and I’m going to try to make something happen or think about something or see what I can push forward. It’s your job, and that’s how I feel. I feel like I’m a worker.

More of Eileen Cowin’s work can be viewed at: eileencowin.com

Article edit by Mark Daybell

THE PRACTICE OF CREATIVITY

©2015-2020 All rights reserved