Artist portrait by Mark Daybell

Artist portrait by Mark Daybell

Candice Lin

Los Angeles based artist

Interview by Mark Daybell

MARK DAYBELL: I’m with Candice Lin in her studio in Altadena, California. It is June 13, 2019. Candice, what initially attracted you to art or art-making?

CANDICE LIN: I always drew as a kid. It was a way to escape into my imagination, and I remember my parents specifically telling me “when you go to college, you’re not going to get a degree in art, right? Because we’re not paying for that”. I was like, “No, why would I do that? That’s a waste of money,” and then I just couldn’t do anything else. I tried to study anthropology, which I found interesting, but I didn’t want to do it as a profession. I just wanted to read the different kinds of texts as a way to think about cultures and histories like I do now in my research.

DAYBELL: Did you receive formal visual arts education?

LIN: I got my MFA in New Genres at SFAI. New Genres encompassed video, installation and performance, and for my undergraduate at Brown University I did a double BA in studio art and art semiotics, which is kind of like a theory degree.

DAYBELL: Can you tell me about your art work?

LIN: I work in multiple mediums usually in the form of installation that has some audio or video components mixed with sculptural elements, also bringing in drawing, and sometimes print making. I work with marginal or lesser known histories that address issues of race, gender, and sexuality, looking at colonial histories or plantation economies, and the ways that these histories continue to live into the present. I often will use unconventional materials like sugar, or tea, or make a mold or stain as a way to bring the histories into physical contact with the viewer through the materiality of the work.

For instance, in System for a Stain, a sculptural installation made of makeshift wooden stands and a DIY looking system that has a basin about the size of my outstretched body. It’s filled with this liquid that’s a mix of tea, sugar, opium poppy seeds and cochineal, which was an insect that makes red dye and was an important colonial trading good. These materials are steeping, distilling, and fermenting and the liquid is circulating through a system of pumps, hot plates, copper boiler, plastic tubing, and porcelain vessels. They traverse the gallery space through the system of clear tubing, and then gradually spill into another room which is empty except for an audio piece that relates elements of my historical research in an anecdotal fictionalized way, through a text that I wrote. Slowly over the three months, this red stain accumulates. It started out really beautiful orange-pinky- red, and then by the end of the three months, it was like this menstrual brown-red, with a skin on it from the fermentation process, and it smelled really pungent. That’s something you don’t see in the images of my work is that often you come into an installation and before you see anything you are hit by a smell, either the smell of plants boiling, or fermenting urine. System for a Stain had a really vinegary smell, because of the fermentation of the tea and sugar.

System for a Stain ©2016 Mixed media Commissioned by Gasworks | London

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Andy Keate

System for a Stain ©2016 Mixed media Commissioned by Gasworks | London

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Andy Keate

System for a Stain ©2016 Mixed media Commissioned by Gasworks | London

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Andy Keate

DAYBELL: Are there reoccurring themes in your work?

LIN: A lot of my work deals with the politics of power and representation.

“I work with marginal or lesser known histories that address issues of race, gender, and sexuality, looking at colonial histories or plantation economies, and the ways that these histories continue to live into the present.”

DAYBELL: What does your practice of creativity involve? Can you talk about some specifics?

LIN: My practice is a heavily research-based process, but I think of research broadly. I include my hands playing with material as a kind of research, as well as reading a lot—usually history or cultural theory that acts as a kind of node that I build an idea off of. But it can also go the other way. Sometimes I get really interested in the way a material feels or behaves and I begin learning about it after working with it physically. I did a whole three-part exhibition focused around porcelain that began from the material.

DAYBELL: Talk about how you begin a project.

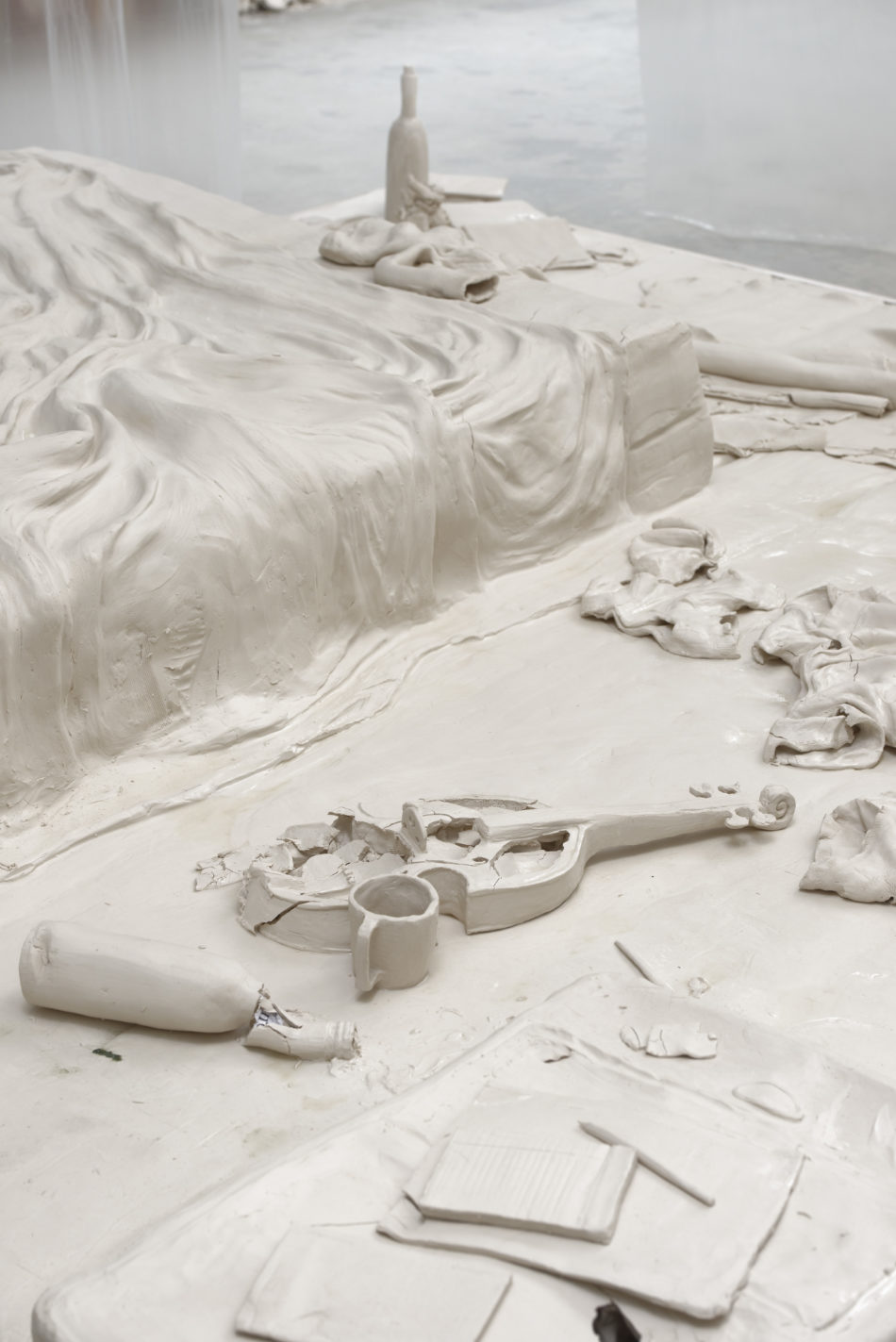

LIN: Recently the work has been site-specific and begins with researching the location of an institution that has invited me to propose an exhibition. I do a site visit and research something about that site—its location, geography, politics, or material production–and then I start to think about what am I interested in independently, and how it overlaps with that location. I was doing a series around porcelain, called A Hard White Body. The title comes from an 18th century European description of the superior hardness and unbreakableness of porcelain. I was invited to do the show at Bétonsalon in Paris. I was interested in the European context, and I knew the show would travel to Portikus in Frankfurt. So I wanted to think about the circulation of this exhibition and how it mirrored the circulation of and fascination with porcelain in the 17th century to 19th century.

My research in Paris brought me to the history of Jeanne Baret, a French peasant woman knowledgeable about plants, who in the 18th century is thought to be the first woman to go around the globe. James Baldwin and his time in Paris also was something I was thinking about—ideas of exile and home, and so these things came together in an associative way in my research about the place, and I found ways they were related even though they were more obviously very different in subject and time period.

DAYBELL: How does your site visit and other research transform into an aesthetic?

LIN: With A Hard White Body, I was reading these very strange racialized description of porcelain as being a hard, impregnable, superior body that was pure white and impossible to stain with foreign products such as coffee and tea. I wanted to use porcelain in a way that was broken, stained, was not impregnable but porous. I wanted to make something that is not fired, that refuses the racialized narrative around it. Then, I was reading essays about James Baldwin’s time in Paris at the same time I was reading about these descriptions of the ship cabin Jeanne Baret traveled around the globe in. The small ship cabin sounded really similar to the way the Paris apartment is described in Baldwin’s novel, Giovanni’s room, the first book I read as a teenager that resonated with my queer identity. So from these different elements of research coming together, I had the idea to make a room out of unfired porcelain that imagined what the room that the character Giovanni lived in looked like, as well as what Jeanne Baret’s ship cabin might have looked like, using objects—violin, maps, jars and bottles—from those descriptions.

Also, I was thinking a lot about caretaking as I was traveling and being dependent on other people and thinking about the larger communities of care taking that exist and have existed, as well as the erasure of that care. And I was also thinking about implication, my own implication—as I traveled I felt selfconsciously aware of the impossibility of escaping or standing outside of what one is looking at critically. I wanted to make an installation that highlighted these acts of implication and caretaking so the porcelain room I created had a liquid component that was used to keep the porcelain wet—to keep it from cracking and falling apart—and this liquid was urine that was donated by the people who worked there and myself. The urine was distilled into sterilized water, which still smelled like piss and had various flavors, not quite like water. When you walked in, you saw a urinal and it smelled like piss, and you were invited as a visitor to donate your urine as well. We actually ended up with liters and liters of piss—more than we could use! This distilled urine was steeped in plants relating to the history of Jeanne Baret and her bio-prospecting in the colonial expedition she participated in in 1766-1769. That water was pumped up and misted onto the sculpture, almost in a futile attempt to take care of this lifesize bedroom made out of porcelain to keep it from drying and falling apart. It didn’t work. It cracked, because that’s the thing about porcelain, it cracks the most easily of all the clays. It got stained overtime, a yellowish color, and it grew mold and mushrooms, which I didn’t expect but was pleased by.

So, I set out the parameters of what I hoped to accomplish, which was to refute the language around porcelain, which valued it for reasons aligned with white supremacy, despite it being of Asian origin. But I didn’t have a clear outcome of what the installation was going to be, or have full control over it. Then it did its thing. The fragments of the porcelain room later traveled and were recomposed in different installations in Frankfurt and Chicago. At Portikus, the fragments became a landscape for silkworms to live and die upon. At the Logan, the fragments were flooded in a pool of porcelain slip that slowly molded all the drawings and research material.

A Hard White Body, a Soft White Worm ©2018 Installation view. Portikus | Frankfurt

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Helena Schlichting

Detail of: A Hard White Body, a Soft White Worm ©2018 Installation view. Portikus | Frankfurt

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Helena Schlichting

A Hard White Body, a Porous Slip©2018 Installation view. Portikus | Frankfurt

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Helena Schlichting

A Hard White Body / un corps blan exquis ©2017 Installation view. Bétonsalon-Center for Art and Research | Frankfurt

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Aurélien Mole

Deatil of: A Hard White Body / un corps blan exquis ©2017 Installation view. Bétonsalon-Center for Art and Research | Paris

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Lila Torquéo

DAYBELL: How do you record your ideas for projects?

LIN: I make sketches that I feel don’t make any sense to anyone but me. I would never show those, because I don’t think they translate, and then I do make more elaborate drawings or digital mockups for the institution that I’m making the show for, and diagrams about if they’re fabricating part of it for me, telling them how to build it. And I’ve been working on my first two books this year. That’s been an interesting process because I always think it would be nice to record the thinking process that goes into all the research and shaping of these bodies of work but they usually end up being disorganized files in various folders lost on my computer. But I think that the books will organize this research and become exactly that, a way to record and show my thought process.

“I think of risk as an opportunity, because I’m really interested in being an artist that is not interested in mastery, but in propositions that start conversations with material and history and the people who come to see the art.”

DAYBELL: How does risk factor into your practice?

LIN: I think of risk as an opportunity, because I’m really interested in being an artist that is not interested in mastery, but in propositions that start conversations with material and history and the people who come to see the art.

In terms of financial risk, I feel like I’ve been lucky to not ever make work where I am depending on selling it because I’ve always been fortunate enough to have other jobs—artist assisting, teaching, etc.—that pay for my costs of living. I think that allows freedom, and allows me to make things that are more about what intellectually stimulates me and materially feels interesting to me. I’m lucky to have a gallerist who doesn’t ever pressure me to make sellable work, but supports and believes in the larger vision.

Recently, the idea of riskiness has come up around subject matter that’s really loaded. I’m often working with racialized materials or racial stereotypes as a way to critique these histories and ideas, and address that history and the way it’s still present in our contemporary landscape. There’s a risk of it being misunderstood or of recreating the same violence as the thing you are critiquing. I think because of that, I address that kind of risk by trying to always have some statement or audio piece, or video piece that makes the content and the histories that I’m dealing with clear without being overly didactic.

Those are the three main kinds of risk I can think of.

DAYBELL: For “Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon” at the New Museum, didn’t you fill the museum with a mist? That seems like a risk.

LIN: That was a collaborative piece with Patrick Staff. We made hormonal fog, from a tincture of herbs that are anti-androgens, so they suppress testosterone and increase estrogen. Then, we vaporized it using a hacked commercial fog machine. The actual effect on your body would probably be less than you already have by drinking beer and eating tofu. Processed food, for instance, is extremely high in estrogen. It’s more of a provocation than an actual risk, but it was interesting that some of the guards complained, and they were like, “I don’t want to be in the lobby floor where I’m getting all this estrogen in my body.” We explained to them that it’s not a synthetic estrogen that’s actually being absorbed in the skin, but it’s a plant tincture that is equivalent to, or less than what they probably already have absorbed.

DAYBELL: How does the history of art or art-making influence your process?

LIN: It’s funny because I feel like the history of art was never something I was that specifically interested in. I’m interested in the history of the world, which I guess has elements of art history in it. I deal very much with the historical, but rarely would the point be about referencing another artwork, although some people read the urinal at the Betonsalon exhibition that way. But I wasn’t really focused on Duchamp or Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, but more on erotic and survivalist subcultures recuperating urine as a precious material and using it for an act of care.

La Charada China, Installation view Hammer Museum | Los Angeles ©2018

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber

Deatil of: La Charada China, Installation view Hammer Museum | Los Angeles ©2018

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber

Deatil of: La Charada China, Installation view Hammer Museum | Los Angeles ©2018

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber

DAYBELL: Do you make art every day?

LIN: No, I have too busy of a schedule. I try to make sure I at least have a full studio day one day a week. But I’d love for it to be more.

“I like to be in the space of knowing what the general framework around what I’m trying to do is, but I like there to be room for the unexplainable.”

DAYBELL: How do you recognize a good idea?

LIN: I don’t know if I know how to recognize a good idea. I know how to recognize an idea that I’m excited about. I know how to recognize when it’s getting bad, when I’m over controlling its expression. I think sometimes when I know what I’m doing and what I wanted to communicate, it starts to feel limited by my mind and my abilities. I like to be in the space of knowing what the general framework around what I’m trying to do is, but I like there to be room for the unexplainable. I think we make art because it’s its own thing. I think if you can explain it in a well-written statement, it’s maybe lacking something. It’s not working on the senses the way only an art work can do. When the work is becoming the same as the statement, I’m like, “Oh, this feels boring and bad, safe and limited,” and I know I need to change it so the work can have some other thing that’s happening in it.

DAYBELL: Do you need to be in your studio to access creative ideas or solutions?

LIN: No. I think I get a lot of my creative ideas when I’m in…what would you call it… suspended boredom. I get a lot of ideas when I’m commuting, because I’m stuck and so I can’t be answering my e-mail and occupying my mind. My mind is in this weird limbo state, and then ideas just drop in, and I’m like, “Oh yeah, I want to do that,” and I get excited. I even have this notepad that I’d scroll things on, on my steering wheel when I’m driving, because I get a lot of ideas when I’m driving or right before I fall asleep.

DAYBELL: How do you know your project is finished?

LIN: When the deadline comes. I feel like the projects could be endless. A lot of it is not complete but done for now, done for this iteration. It takes the pressure off, and it also makes me remember that art making is just one aspect of living that is ongoing. I always tell my students this because I think sometimes they feel like, “Oh my God, I’m making this show and it has to be perfect, and it has to be resolved,” but I feel like I have let go of that and I just think of each piece as little slices of a bigger ongoing process.

DAYBELL: Do you find the creating process more of a challenge or an asset?

LIN: It’s not a challenge. I don’t know if it’s an asset. It’s my joy in living.

DAYBELL: Do you ever hit a creative wall? How do you break through it?

LIN: I have not reached a creative wall ever, actually. I mean, I think there’s always a range of more ideas are flowing, or less ideas are coming and it’s more about a balance between stress, work, and life.

DAYBELL: What inspires or informs your creativity?

LIN: I think it’s driven a lot by what I care about in the world. The stuff I research has to do with what I’m interested in creating and thinking about. Which for some reason, always goes back to these same themes, themes around the politics of power at stake in the representation of race, sexuality, or gender.

The inscrutable speech of objects, Installation view Weingart Gallery | Occidental College ©2019

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber

Detail of: The inscrutable speech of objects, Installation view Weingart Gallery | Occidental College ©2019

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber

Detail of: The inscrutable speech of objects, Installation view Weingart Gallery | Occidental College ©2019

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber

Detail of: The inscrutable speech of objects, Installation view Weingart Gallery | Occidental College ©2019

Courtesy the artist and Ghebaly gallery | Los Angeles Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber

DAYBELL: What advice would you give emerging artists?

LIN: If you’re driven by ideas of success or recognition, it’s going to be a really hard road. There are other professions that would really let you reach those goals a lot easier. Not to be discouraging, but the chances of being recognized or rewarded in the art world are small, and they’re also fickle. I think your sense of gratification needs to come from inside.

More of Candice Lin’s work can be viewed at: ghebaly.com/work/candicelin

Article edit by Mark Daybell

THE PRACTICE OF CREATIVITY

©2015-2020 All rights reserved