Artist portrait by Mark Daybell

Artist portrait by Mark Daybell

Brian Moss

Los Angeles based artist

Interview by Mark Daybell

MARK DAYBELL: It is July 16, 2019. I’m here with Brian Moss in his studio in Santa Monica, California. Brian, what initially attracted you to art or art-making?

BRIAN MOSS: I remember a clash. Specifically, I remember a clash between what I wanted to do on some project, I think it was in fourth grade. Maybe it was fifth grade. Mr. Molzan, I think was his name. It was one of those things. They give you a can, like a soup can or a soda can or something. We were supposed to make a bird out of it, attach wings to it and so on. They wanted the wings to come out of the middle of the can. I came up with this way of having the wings come out of the ends of the can and go up and go down. I remember my teacher was like, “No, no, no. This is not following the instructions.” My mother somehow found out about this and went in and read him the riot act. Like, “Don’t you impede my son’s creativity.” I think it probably somewhat came out of that. I mean, everybody draws when they’re a kid, right?

DAYBELL: Right.

MOSS: My mom dragged me to museums in every city that we visited throughout my whole childhood. Half the time, I was like, “This is really boring. Let’s get out of here,” but clearly something caught on. She started sending me to art classes at this local neighborhood art center in Cheltenham, outside of Philadelphia. I had people say, “You’re good,” and “you enjoy doing it.” Next thing you know, that’s what you do. I think it was also partly that whole myth of what an artist is. I think I kind of fell in love with that in high school. Like, “Yeah, I’m going to be an artist. I’m a rebel.” I mean, it’s obviously bullshit.

“I’m interested in why people hate each other. I’m interested in what keeps people in their groups as opposed to part of a larger whole. I’m interested in the experience of a diaspora as a Jewish guy whose grandfather came here from Ukraine in 1920-something, and was basically chased out of his village along with the rest of his family.”

DAYBELL: Did you receive formal visual arts education?

MOSS: Definitely. I went to a high-level high school art program. I went to Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia as an undergrad. I have a BFA. I have an MFA from CalArts. I did the whole art school thing, even though Tyler was part of Temple University. In a sense, I don’t really feel like I went to a university. I don’t have a traditional liberal arts education. I have a fine arts education, 100%.

DAYBELL: Can you tell me about your artwork?

MOSS: My artwork is not medium-specific. My BFA is in painting but my MFA is in photography. I use a lot of found objects in my work. I think in terms of installations and relationships. I still use drawing to this day, although it’s not anything like the drawing that I did when I was in grade school. My work is kind of all over the place medium-wise, and then content-wise, I would say, I’m interested in social issues. I’m interested in why people hate each other. I’m interested in what keeps people in their groups as opposed to part of a larger whole. I’m interested in the experience of the diaspora as a Jewish guy whose grandfather came here from Ukraine in 1920-something, and was basically chased out of his village along with the rest of his family. I’m interested in that stuff.

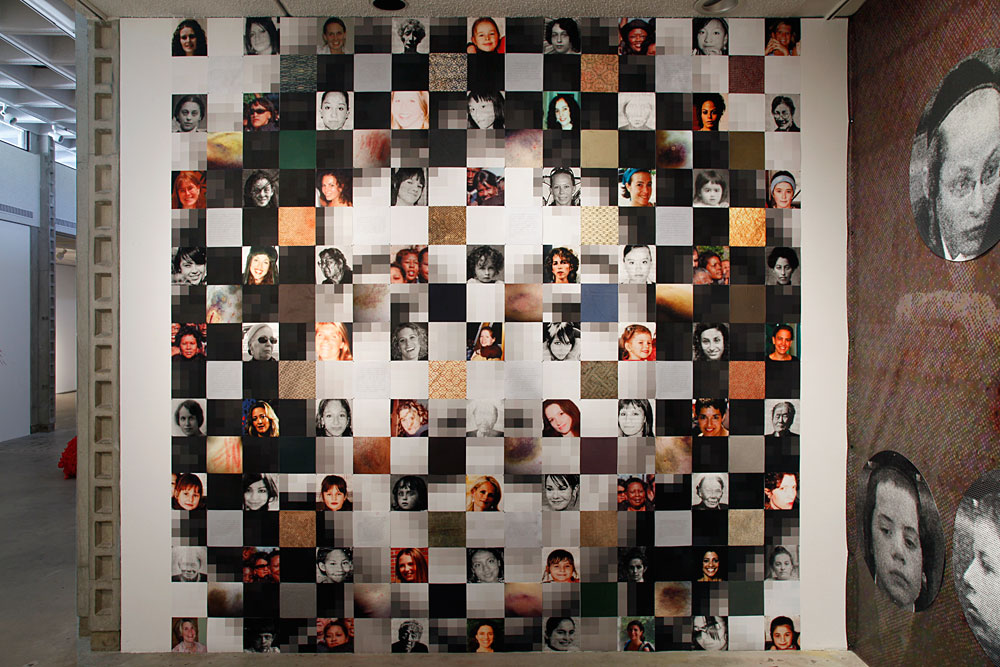

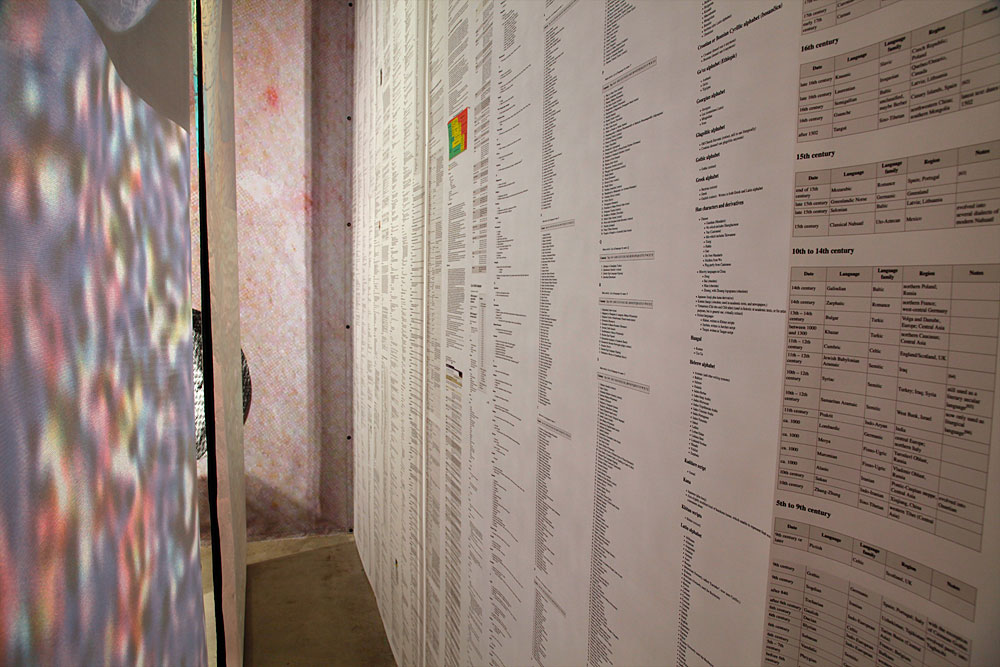

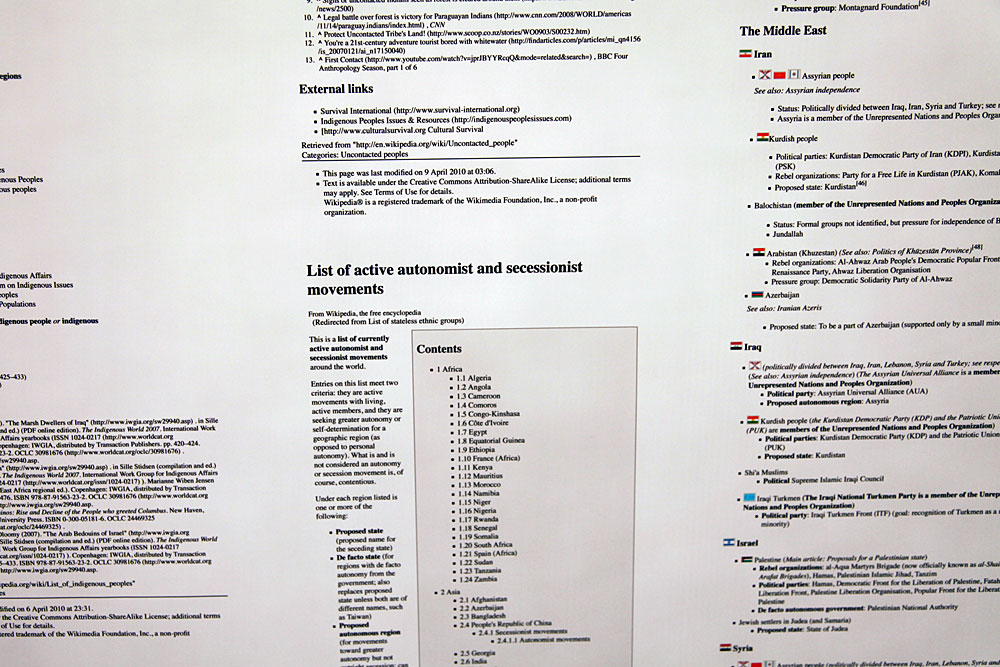

The Theory of Everything was a multi-part project created for the 2010 COLA Grant Exhibition at the Los Ageles Municipal Art Gallery.

These found news images served as source and inspiration for much of the work.

This was the initial entry into the installation, which had another roomthrough the door to the right.

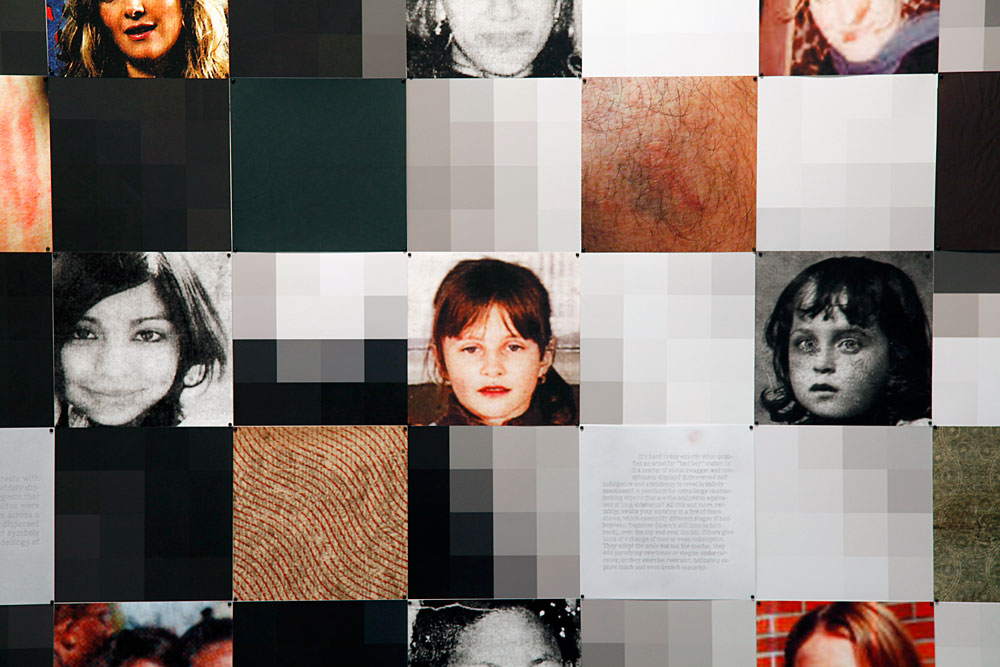

detail of Untitled (schoolchildren) 2010

i.d. 2010

289 pigment prints and 20 graphite on vellum drawings (8.5 in. squares each), map tacks, 144 in. square

detail of i.d. 2010

detail of Untitled (area of detail) 2010

detail of Untitled (area of detail) 2010

Perception Cards, 2002-03

3 channel Flash animation, 3 DVD players and monitors, dimensions variable

installation view of Theory of Everything, 2010

Untitled (centering) 2010 a series of quicktime movies created for the installation: Theory of Everything

DAYBELL: What does your practice of creativity involve? Can you talk about some specifics?

MOSS: I’m not sure that I have a process per se. In some ways for me, I feel like an idea is never done. It’s always sort of evolving, because I’m evolving and my understanding of everything, including myself, is evolving. But things just pop like sparks, right? Things happen. It’s usually seeing something or reading something. It’s not research-based in that respect, but I read the newspaper voraciously, mostly The New York Times. A lot of stuff generates from that.

DAYBELL: You work as both a fine artist and commercial artist. Can you speak about how your process might differ between the two types of work?

MOSS: I’m generally hired to do documentary-type photography work. If someone has an artwork and they want it documented, I shoot it. The work ends up on the web, in a book, portfolio or wherever. I am hired to capture the work and the representation has to match the reality.

Artist Jody Zellen

Artist Jody Zellen

MOSS: But other times, just this year for instance, I worked on the COLA catalog. I made portraits of all the artists for the catalog. That was a little different, because it wasn’t just about making a document. It was also approaching it somewhat creatively. My client was the Department of Cultural Affairs, but then my client in another sense is the person I’m taking the picture of. Even though they’re not paying for it, this is a service and a courtesy to them, because they won this grant that recognizes them as significant artists in Los Angeles.

DAYBELL: Do you do something like a client brief? Do you ask them what they’re looking for?

MOSS: First, there was a back and forth between myself and Joe Smoke at Cultural Affairs. It’s like, “Joe, what’s the approach here? How much room is there to play here? What do you really want? Can I do this?” “No, I don’t think we really want pinhole photos of everybody. Let’s go for a more traditional portrait.” “But does it have to be in the studio?” “No, it doesn’t have to be in the studio.” We kind of worked that out, and then I went to each of the 14 artists and I went through the same thing. “Well, here’s the options. We could do this, we could do this. There’s some parameters here beyond which we don’t really want to stretch.” Some people push more and some people are like, “Yeah, whatever.” They don’t care. That kind of job is much more akin to art-making for me, in that you’re dealing with a bunch of elements that you don’t really have any control over. I like that challenge. But in the end, it’s like, “Are these portraits art? Are they my art?” Not really. I’m proud of them, I like them, but it’s a job. It’s a creative job, but it’s still a job. In that sense, yeah, it’s different. I have high standards for myself, extremely high standards. If it doesn’t look the way I want it to, I’m not happy, I’m going to keep working on it until I get something that I like, but yeah. It’s different.

Sabrina Gschwandtner | 2019 COLA Individual Artist Fellowship for Art

Suzanne Lummis | 2019 COLA Individual Artist Fellowship for Poetry

Dwight Lummis | 2019 COLA Individual Artist Fellowship for Music

Peter Wu | 2019 COLA Individual Artist Fellowship for Art

“If it’s just self-centered or about making something pretty and it doesn’t really comment in any way on the reality we live in, I’m just not interested in working on it.”

DAYBELL: How do you recognize a good idea?

MOSS: It’s kind of what engages me enough to keep working on it. The why, I think is who knows? It’s the temperament, the mood you’re in, the timeframe, what else is going on around you in your life, whether it’s at work, or at home, or emotionally, or whatever. Friendships, parents, etc. I would say, again, the one thing that I feel like I don’t do enough of is spend time in the studio working. There’s plenty of good ideas I don’t have time to work on. There’s probably a whole bunch of other bad ideas, written down somewhere that I just forget about. Once in a while I look at it, I go, “Yeah, that wasn’t so interesting.” Why? What is it about it? That’s harder to put my finger on. I think, ultimately, it’s got to have a kind of broader impact. It’s got to make some kind of statement about the condition of the world that we live in at this point in time. That’s important to me. If it’s just self-centered or about making something pretty and it doesn’t really comment in any way on the reality we live in, I’m just not interested in working on it.

DAYBELL: What is the role of chance in your creative practice?

MOSS: The degree to which I engage chance is in keeping with what I think is a proper attitude toward living and life. Which is you should be aware. You should be open. You should be out looking. Don’t be closed off. Be open and see what’s around you. But then it was really funny, because I was having a conversation a couple days ago with my neighbor who’s in a sort of bad situation with a roommate that he let into his house. Now he’s trying to get rid of them. We were talking for an hour and a half. At the end of the conversation, he pulls out the Book of the I Ching and this little leather pouch with the three coins. He’s like, “It’s magic. It really works.” I’m like, “Yeah, that’s okay. I don’t know…” but then I’m also telling him, “Well, people like Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage and Merce Cunningham, they actually used this in the construction of their work.” But I’m not necessarily willing to go there.

DAYBELL: Do you make art every day?

MOSS: No. Absolutely not. Sometimes I don’t make art every month.

DAYBELL: Do you need to be in your studio to access creative ideas or solutions?

MOSS: No.

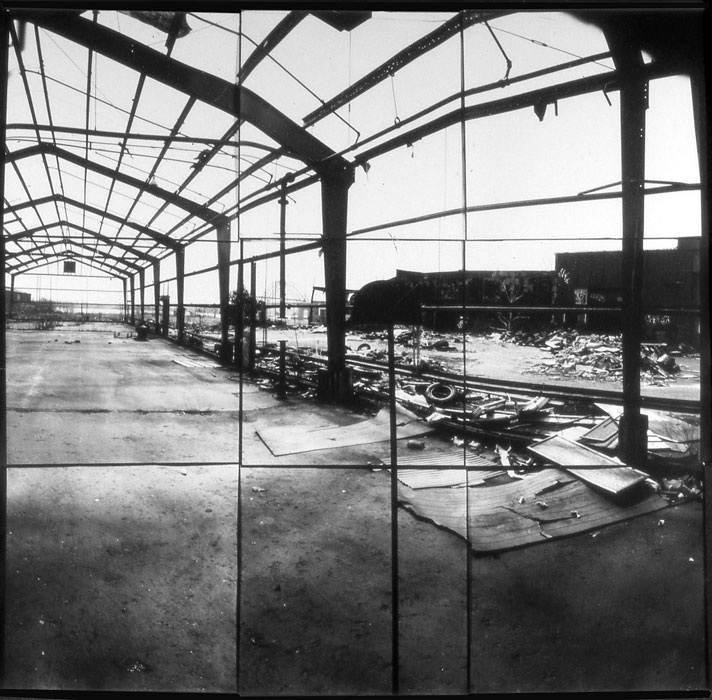

Dodge Steel Castings, Inc. 1992 | silver-geltin print, 120 in. square

Dodge Steel Castings, Inc. 1992 | silver-geltin print, 120 in. square

Dodge Steel Castings, Inc. 1992 | silver-geltin print, 120 in. square

DAYBELL: How do you know when a project is finished?

MOSS: When the show has to open, the project is finished. But in a sense, it’s never finished. Many projects can always be built upon. But, it’s also, “Yeah, okay. I did that. It’s done. Leave it alone. There’s nothing to do to it now.”

I mean, I don’t know when a project is finished. Let’s put it that way. I think that’s an open-ended question that I can’t really answer. I don’t know. There’s no certainty there. My Dodge Steel pinhole photos from Philadelphia from 1991 to ’93, yeah, that project is finished, but that’s a long time ago and that’s why it’s finished. Although, it’s not necessarily because I was actually thinking recently, “I’ve got to write a Guggenheim grant to go back to Philadelphia and take pictures in all the places that I shot in the ’80s and the ’90s.” Shoot them now, but then look for original photos of those buildings from when they were built, whether they were built in 1800s or 1900s. Then present this as a book. Like, “This is Philadelphia then—then, and now.” How would I shoot them differently now? Because I would. I would shoot them completely differently than I did back when I was making medium format black and white photos in Philadelphia in the mid-’80s and the early ’90s. I’m not that same photographer anymore. Going to CalArts changed my understanding of what photography is and how you can approach photography differently.

DAYBELL: Do you find your creative process a challenge or an asset?

MOSS: I find the idea that I can say to myself, “I am an artist,” as an asset. That I think like an artist. I consider myself an artist. I certainly find that to be an asset. Yeah, it’s definitely a challenge, as well. I mean, it’s clearly both, because if you’re going to call yourself that, if you’re going to talk the talk then you got to walk the walk. I was thinking, “Oh, Mark’s going to come over here and who am I kidding? I’m not an artist. I don’t make enough art to really be called an artist.” A lot of people would say, “Oh, you’re full of shit. You’re just a pretender. You don’t make art. You’re not an artist.” In some ways, they would be right. People who work every day in their studio, they’re really fulfilling the role of an artist.

I don’t do that most of the time. It would be hard for me to argue against that. On the other hand, this is what I am. This is who I am. This is not necessarily what I do all the time, but it’s certainly how I think. I think that’s maybe more important in some respects—that I approach the world, I approach all the stimuli and input that I get around me as an artist. Like, “Is that true? Do I believe that? Does that make sense?” I’m critical of it, but I’m critical in a productive way. Like, “Yeah, okay. How does that work?” I like to understand things. I like to learn things. I like to make things.

011-10-01 17.53.02 L.A. Mart, S. Broadway & W. Washington, LA/2012-12-19 15.20.08: Ann Hamilton @ Park Avenue Armory, NY, 2013

Epsom Ultrachrome Print on archival paper, 8 x 19 in.

2012-04-29 14.35.55: MOCA, W. 3rd & Grand, LA/2011-11-12 15.17.32: Pae White @ 1301 PE, LA 2013

Epsom Ultrachrome Print on archival paper, 8 x 19 in.

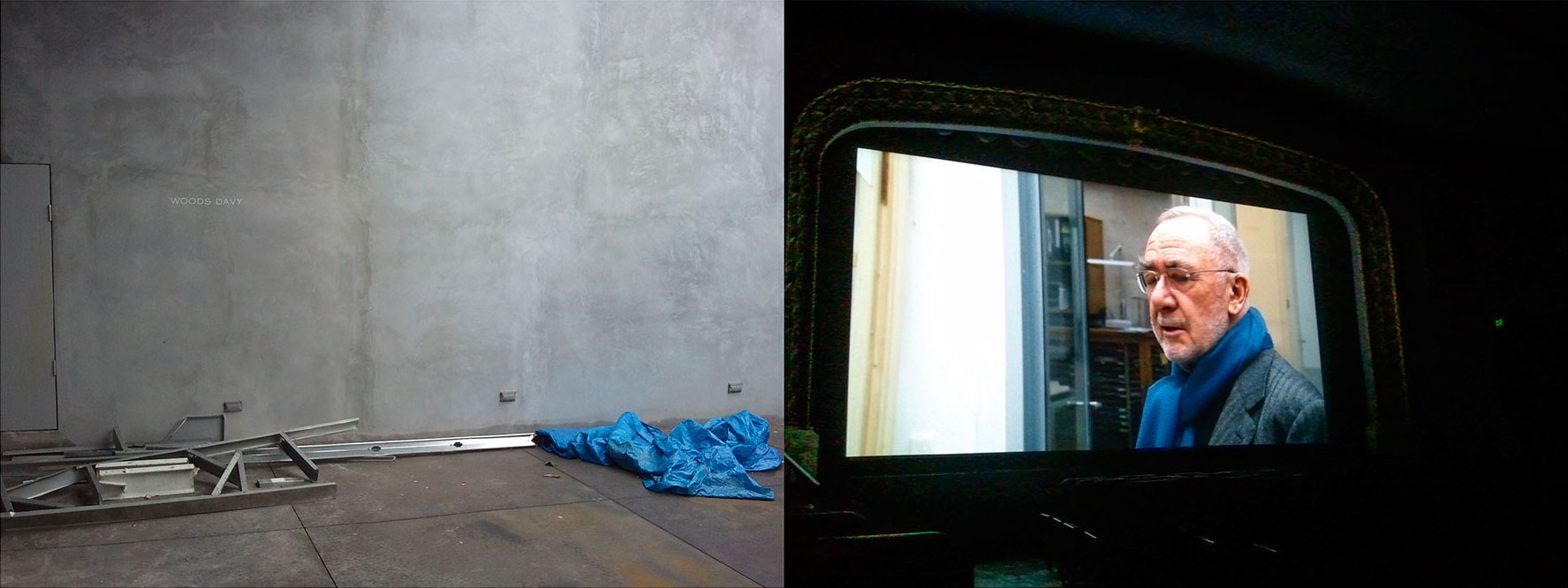

2011-11-12 14.11.54: Woods Davy @ Craig Kull, SM/2012-06-25 18.07.23: :Gerhard Richter Painting” @ Laemmle Royal, LA 2013

Epsom Ultrachrome Print on archival paper, 8 x 19 in.

2011-08-11 19.26.58: Bay Street, SM/2011-05-21 12.34.58: J. Golden mural, Ocean Park & Lincoln, SM 2013

Epsom Ultrachrome Print on archival paper, 8 x 19 in.

2012-06-16 14.21.12: W. 22nd Street, NY/2012-11-26 13.14.18: Kosciuszko & S. Hope, LA 2013

Epsom Ultrachrome Print on archival paper, 8 x 19 in.

2011-11-19 14.27.56: WSS Shoes, La Cienga & Cadillac, LA/2012-09-08 17.56.07: Retna mural, La Cienga & Smiley, CC 2013

Epsom Ultrachrome Print on archival paper, 8 x 19 in.

DAYBELL: Where do you look for creative inspiration?

MOSS: It’s just in my head. It’s always here. I don’t think I look anywhere for creative inspiration per se. I mean, god knows I see enough shows. I regularly tell people, “I probably like 10 to 20% of what I see.” Of that 10 or 20%, how much of that inspires me? Probably another 10% of that. But then, there’s inspiration everywhere. I mean, walking down the street, you stumble on shit all the time and it’s inspiring. I don’t know why or how, or maybe it comes from that sort of open-mindedness that I talked about before. I think it probably does, at least partly. I think it’s just our world, the world is so complex, and amazing, and unbelievable. Where is there not inspiration?

“Be open-minded, but be true to yourself. How do you maintain that balance? Because being open-minded means listening to others, and taking into consideration what they have to say, and how they think, and how they feel, and what their existence is, what their life is like. But also, don’t lose yourself in others.”

DAYBELL: Are you satisfied creatively?

MOSS: I’m satisfied with myself as a creative person. No, I am not satisfied with my creative output. No, I am not satisfied with the possibility of creative opportunities. No, I am not satisfied with the degree to which the world shows any interest or places any importance on creativity and art in and of itself.

DAYBELL: What advice would you give to an emerging artist?

MOSS: Be open-minded, but be true to yourself. How do you maintain that balance? Because being open-minded means listening to others, and taking into consideration what they have to say, and how they think, and how they feel, and what their existence is, what their life is like. But also, don’t lose yourself in others.

The other thing I guess advice-wise is, what do you want? What do you want and what do you need? Those are really good questions to be able to distinguish.

DAYBELL: Anything else you would like to add?

MOSS: If you really want to do this, you need to understand the other side of it. Not just the art-making side but how art functions in the bigger world. How does the art business work? How do galleries work? How do collectors work? How do museums work? How does nationalism and art work? What is all that? I feel like I never really knew anything about that until I came to LA when I was almost 30. That was kind of too late. I should have learned that a lot sooner. On the other hand, if I could have been an astronomer or a scientist instead, I feel like that probably would have been the better choice, because being an artist is completely thankless. In a lot of ways, it’s kind of worthless and useless. You better love it. You better love it, because if not, you’re wasting your time. I like thinking that way. I like living that way. I don’t have to get rewarded for it, but that’s me. I’m one in eight billion. I’m small. I embrace that smallness.

More of Brian Moss’ work can be viewed at: briancmoss.com

Article edit by Mark Daybell

THE PRACTICE OF CREATIVITY

©2015-2020 All rights reserved